- Home

- Timothy Leary

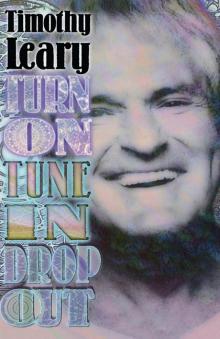

Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out Page 3

Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out Read online

Page 3

The social reality in which we have been brought up and which we have been taught to perceive and deal with is a fairly gross and static affair. But it misses the real excitement. The real hum and drama, the beauty of the electronic, cellular, somatic, sensory energy process have no part in our usual picture of reality. We can’t see the life process. We are surrounded by it all the time. It is exploding inside of us in a billion cells in our body, but most of the time we can’t experience it. We are blind to it. For example, how do we know when another person is alive? We have to poke his robot body and listen to his heart, look for some movement. If he breathes, he is alive. But that is not the life process. That is just the external symptom. It’s like seeing that the car moves, and from the fact that the body of the car moves, inferring that the motor is going inside. We can hear the car motor, we can brake, but we can’t tune in on the machinery of life inside ourselves or around us. Now at this point you must be thinking, well, poor Leary, he has gone too far out. But really I don’t think that it should be this difficult to accept logically the fact that there are many realities and that the most exciting things that happen, cellular and nuclear processes, the manufacture of protein from DNA blueprints, are not at the level of our routine perception. And for that matter, that the most complex communications, the most creative processes, exist at levels of which we are not ordinarily aware.

Let’s take an analogy. Suppose that you had never heard of the microscope, and I came before you and said, “Ladies and gentlemen, I have an instrument which brings into view an entirely different picture of reality, according to which this world around us which seems to have solidity and symmetry and certain form is actually made up of organisms, each of which is a universe; there is a world inside a drop of water. A drop of blood is like a galaxy. A leaf is a fantastic organization perhaps more complicated than our own social structure.” You would think that I was pretty far out, until that moment when I could persuade you to put your eye down to the microscope, show you how to focus, and then you would share the wonder which I had tried to communicate to you. All right, we know that cellular activity is infinitely complex.

We tend to think of our external, leatherlike skin body as the basic ontological frame of reference. The center of our universe. This foolish egocentricity becomes apparent when we compare our body with a tractor. We usually think of a tractor or a harvesting machine as a clumsy, crude instrument which just organizes and brings food for us to feed our mouths. But from the standpoint of the cell, the animal’s body, the human being’s body, your body, is a clumsy instrument, the function of which is to transport the necessary supplies to keep the cellular life process going. And we realize, when we study biology textbooks, that our body is actually a complex set of soft-divine machines serving in myriad ways the needs of the cell. These concepts can be a little disturbing to our egocentric and our anthropocentric point of view.

But then we’ve just started, because the fellow with the electron microscope comes along. And he says, “Well, your microscope and your cell is nothing! Sure, the cell is complicated, but there’s a whole universe inside the atom in which activities move with the speed of light, and talk about excitement, talk about fun, talk about communication, well, now here at the electron level we’re just getting into it.” And then the astronomer comes along with his instruments, and off we go again!

The interesting thing to me about this new vision of many realities that science confronts us with (however unwilling we are to look at it) is this: the closer and closer connection between the cosmology of modern science and the cosmology of some of the Eastern religions, in particular, Hinduism and Buddhism. I have a strong suspicion that within the next few years, we are going to see many of the hypotheses of our Christian mystics and many of the cosmological and ontological theories of Eastern philosophers spelled out objectively in biochemical terms. Now, all of these phenomena “out there” made visible by the electron microscope, the telescope, are wounding enough to our pride and our anthropomorphism (which Robert Ardry calls the “romantic fallacy”), but here, perhaps the most disturbing of all, comes modern pharmacology. Now we have evidence which suggests that by ingesting a tiny bit of substance which will change biochemical balances inside our nervous system, it’s possible to experience directly some of the things which we externally view through the lenses of the microscope.

I will have more to say about the applications and implications of educational chemistry shortly. I’d like to stop and consider briefly the social-political and educational problems which are the subject of our symposium. We have told each other over and over again during the last two days of the conference that we’re in pretty bad shape. Well, I’m not quite that pessimistic. What’s in bad shape? The cellular process isn’t in bad shape. The supreme intelligence, if you want to use that corny twentieth-century phrase for the DNA molecule, isn’t in bad shape. For that matter, the human species is going to survive, probably in some mutated form. What’s in bad shape? Our social games. Our secular traditions, our favorite concepts, our cultural systems. These transitory phenomena are collapsing and will have to give way to more advanced evolutionary products.

I’m very optimistic about the cellular process and the human species because they are part, we are part of the fantastic rushing flow which has been pounding along from one incredible climax to another for some 2 billion years. And you can’t stay back there, hanging on to a rock in the stream. You’ve got to go along with the flow; you’ve got to trust the process, and you’ve got to adapt to it, and you might as well try to understand it and enjoy it. I have some suggestions in a moment as to how to do exactly that.

We are all caught in a social situation which is getting increasingly set and inflexible and frozen. A social process which is hanging on to a rock back there somewhere and keeping us from flowing along with the process. All the classic symptoms are there: professionalism, bureaucracy, reliance and overreliance on the old clichés, too much attention to the external and material, the uniformity and conformity caused by mass communication. The old drama is repeating itself. It happened in Rome and it happened to the Persian Empire and the Turkish Empire and it happened in Athens. The same symptoms. We’re caught in what seems like an air-conditioned anthill, and we see that we’re drifting helplessly toward war, overpopulation, plastic stereotyping. We’re diverted by our circuses—the space race and television—but we’re getting scared, and what’s worse, we’re getting bored and we’re ready for a new page in the story. The next evolutionary step.

And what is the next step? Where is the new direction to be found? The wise men have been telling us for 3,000 years: it’s going to come from within, from within your head.

The human being, we know, is a very recent addition to the animal kingdom. Sometime around 70,000 years ago (a mere fraction of a second in terms of the evolutionary time scale), the erect primate with the large cranium seems to have appeared. In a sudden mutational leap the size of the skull and the brain is swiftly doubled. A strange cerebral explosion. According to one paleo-neurological theory (Dr. Tilly Edinger), “Enlargement of the cerebral hemisphere by 50 percent seems to have taken place without having been accompanied by any major increase in body size.”

Thus we come to the fascinating possibility that man, in the short infancy of his existence, has never learned to use this new neurological machinery. That perhaps, like a child turned loose in the control room of a billion-tube computer, man is just beginning to catch on to the idea, just beginning to discover that there is an infinity of meaning and complex power in the equipment he carries around behind his own eyebrows.

The first intimation of this incredible situation was given by Alfred Russel Wallace, co-discoverer with Charles Darwin of what we call the theory of evolution. Wallace was the first to point out that the so-called savage—the Eskimo, the African tribesman—far from being an offshoot of a primitive and never-developed species, had the same neural equipment as the literate Europe

an. He just wasn’t using it the same way. He hadn’t developed it linguistically and in other symbolic game sequences. “We may safely infer,” said Wallace, “that the savage possesses a brain capable, if cultivated and developed, of performing work of a kind and degree far beyond what he is ever required to do.” We shall omit discussion of the ethnocentric assumptions (Protestant ethic, primitive-civilized) which are betrayed in this quote and follow the logic to its next step.

Here we face the embarrassing probability that the same is true of us. In spite of our mechanical sophistication we may well be savages, simple brutes quite unaware of the potential within. It is highly likely that coming generations will look back at us and wonder: how could they so childishly play with their simple toys and primitive words and remain ignorant of the speed, power, and relational potential within? How could they fail to use the equipment they possessed?

According to Loren Eiseley (whose argument I have been following in the last few paragraphs), “When these released potentialities for brain growth began, they carried man into a new world where the old laws no longer held. With every advance in language, in symbolic thought, the brain paths multiplied. Significantly enough, these which are most recently acquired and less specialized regions of the brain, the ‘silent areas,’ mature last. Some neurologists, not without reason, suspect that here may lie other potentialities which only the future of the race may reveal.”

We are using, then, a very small percentage of the neural equipment, the brain capacity which we have available. We perceive and act at one level of reality when there are any number of places, any number of directions in which we can move.

Ladies and gentlemen, it is time to wake up! It’s time to really use our heads. But how? Let’s consider our topic: the individual in college. Can the college help us use our heads? To think about the function of the college, we have to think about the university as a place which spawns new ideas or breaks through to new visions. A place where we can learn how to use our neurological equipment.

The university, and for that matter, every aspect of the educational system, is paid for by adult society to train young people to keep the same game going. To be sure that you do not use your heads. Students, this institution and all educational institutions are set up to anesthetize you, to put you to sleep. To make sure that you will leave here and walk out into the bigger game and take your place in the line. A robot like your parents, an obedient, efficient, well-adapted social game player. A replaceable part in the machine.

Now you are allowed to be a tiny bit rebellious. You can have fancy ways of dress, you can become a cute teen-ager, you can have panty raids, and that sort of thing. There is a little leeway to let you think that you are doing things differently. But don’t let that kid you.

I looked at television last night for a few minutes and watched a round table of high school students discussing problems. Very serious social problems. They were discussing teenage drinking. Now the problem seems to be that young people want to do the grown-up things a little too fast. You want to start using the grown-ups’ narcotics before you’re old enough. Well, don’t be in such a hurry! You’ll be doing the adult drinking pretty soon. You’ll be performing all the other standardized adult robot sequences because that is what they’re training you to do. The last thing that an institution of education wants to allow you to do is to expand your consciousness, to use the untapped potential in your head, to experience directly. They don’t want you to evolve, to grow, to really grow. They don’t want you to move on to a different level of reality. They don’t want you to take life seriously, they want you to take their game seriously. Education, dear students, is anesthetic, a narcotic procedure which is very likely to blunt your sensitivity and to immobolize your brain and your behavior for the rest of your lives.

I also would like to suggest that our educational process is an especially dangerous narcotic because it probably does direct physiological damage to your nervous system. Let me explain what I mean by that. Your brain, like any organ of your body, is a perfect instrument. When you were born, you brought into the world this organ which is almost perfectly adapted to sense what is going on around you and inside of you. Just as the heart knows its job, your brain is ready to do its job. But what education does to your head would be like taking your heart and wrapping rubber bands around it and putting springs on it to make sure it can pump. What education does is to put a series of filters over your awareness so that year by year, step by step, you experience less and less and less. A baby, we’re convinced, sees much more than we do. A kid of ten or twelve is still playing and moving around with some flexibility. But an adult has filtered experience down to just the plastic reactions. This is a biochemical phenomenon. There’s considerable evidence showing that a habit is a neural network of feedback loops. Like grooves in a record, like muscles, the more you use any one of the loops, the more likely you are to use it again. If there were time, I could spell out exactly how this conditioning process, this educational process, works, how it is based on early, accidental, imprinted emotions.

So here we are once again. The monolithic, frozen empire is about to fall. We have been in this position many times in the last few thousand years. What can we do about educational narcosis? How can you “kick” the conformist habit? How can you learn to use your head?

We’re all caught in this social addictive process. You young people know that it’s not working out the way it could. You know you’re hooked. You dread the robot sequence. But there is always the promise, isn’t there? There’s always the come-on. “Keep coming. It’s going to get better. Something great is going to happen tomorrow if you’re good today.” It’s not! As a matter of fact, it gets worse, dear robots.

All right, where do we go? What can we do? I have two answers to those questions. The first is: drop out! Go out where you are closer to reality, to direct experience. Go out to where things are really happening. Go out to the frontier. Go out to those focal points where important issues are being played out. Why don’t you pick out the most important problem in the world, as you see it, and go exactly to the center of the place where it’s happening, where it is being studied and worked on? Why not? Someone has to be there, in the center. Why not you?

Now, there’s a risk to this. The first risk is that you’ll lose your foothold on the ladder that you’ve been climbing. You’ll lose your social connection.

Undergraduates come to me very often and say, “I want to go on to graduate school in psychology. Where should I go?” And I always ask them the question, “Why do you want to study psychology?” And as I listen to them, usually one of two answers develops. Answer number one is: “I want to become a psychologist. I want to play the psychology game. I want to be able to play the role and use the terms you use, and I want to be an assistant professor and then an associate professor and then a full professor, and I want to get tenure, and maybe if I’m really ambitious, I might get to be president of the American Psychological Association.” Well, that’s fair enough, and for someone who has that ambition I can give them advice about the strategic universities to go to, like go to Michigan or Yale but don’t go to XYZ.

Some students, though, will say, “I want to study psychology because I want to study human nature” or “I want to find out what’s what.” To do some good. And then I can tell them, well, forget about graduate school. What kind of good do you want to do? Do you want to help the mentally ill? Then get yourself committed to a mental hospital. Stay there for a year or two; you’ll learn more about mental illness in that two years than our profession has learned in a hundred years. If you want to learn about delinquency and reducing crime, go down to the tough section, learn the crime game, learn how to make a man-to-man contact with tough guys, learn from them why they are crooks and criminals. Spend a year in prison, not as a psychologist, but maybe as a guard, or cleaning up the garbage, and you’ll learn more than you will ever learn in a criminology textbook. That is how it goes. The

re is no problem that can’t be best solved and best worked out at this stage of ignorance by getting right into the reality.

Of course, another objection to this suggestion is: “After all, we do need some information and we do need facts and we have to learn them in university courses.” And I say, “Sure, there are existential problems; there are certain times when in trying to solve an existential problem you will want to borrow the experience and the data of previous investigators.” You can use the library, but again, beware, it’s just like a narcotic. Library books are very dangerous addictive substances. Like heroin, books become an end in themselves. I made the suggestion two years ago at Harvard University that they lock up Widener Library, put chains on the doors, and have little holes in the wall like in bank tellers’ windows, and if a student wanted to get a book, he would have to come with a little slip made out showing that he had some existential, practical question. He wouldn’t say that he wanted to stuff a lot of facts in his mind so that he could impress a teacher or be one up on the other students in the intellectual game. No. But if he had an existential problem, then the library would help him get all the information that could be brought to bear on that problem. Needless to say, this plan didn’t make much of a hit, and the doors of the Harvard Library are still open. You can still get dangerous narcotic volumes without a prescription at Harvard.

Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out

Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out