- Home

- Timothy Leary

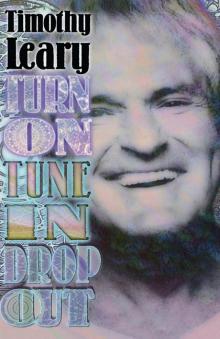

Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out Page 8

Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out Read online

Page 8

His face was glowing, and He was screaming that full-throated God cry that was torn from the lungs of Moses and shrieked by San Juan de la Cruz and which Rosemary and I heard most recently just after our sunrise wedding on the desert mountain top bellowed by the bone-tissue-blood trumpet of Ted Marckland—the eternal, unmistakable cry of the man who has heard God’s voice and shouted back in joyous, insane acceptance. If you’ve ever opened your ears to anyone who has surrendered, wide-eyed, to the sound of God, you know what I mean.

He shook his head and laughed. I can’t say it in words. God, man, I’ve got to learn a musical instrument so I can really say what it sounds like.

Yes, A.O.S.3 carries the official stamp on His skin’s passport that He has been where all the great mystics have been—that point where you see it all and hear it all and know it all belongs together. But how can you describe an electronic rhythm of which 5 billion years of our planetary evolution is just one beat? He is in the same position as every returned visionary—grabbing at ineffective words. But check His prophetic credentials. High native intelligence coupled with a photographic memory. Solid grasp of electronics. Absorbed biological texts. Knows computer theory. Has hung out with the world’s top orientalists and Hindu scholars. Has lived with and designed amplifiers for the farthest-out rock band, the Dateful Gread. As a sniffing, alert, inquisitive mammal of the twentieth century, He has poked His quivering, whiskered nose into all the dialects and systems by which man attempts to explain the divine.

Throughout history the alchemist has always been a magical, awesome figure. The potion. The elixir. The secret formulary. Experimental metaphysics. Those old alchemists weren’t really trying to transmute lead to gold. That’s just what they told the federal agents. They were actually looking for the philosopher’s stone. The waters of life. The herb, root, vine, seed, fruit, powder that would turn on, tune in and drop out.

And every generation or so, someone would rediscover the key. And the key is always chemical. Consciousness is a chemical process. Learning, sensing, remembering, forgetting are alterations in a biochemical book. Life is chemical. Matter is chemical.

His bells jingling as He gesticulates. Everything is hooked together with electrons. And if you study how electrons work, you learn how everything is hooked up. You are close to God. Chemistry is applied theology.

The alchemist-shaman-wizard-medicine man is always a fringe figure. Never part of the conventional social structure. It has to be. In order to listen to the shuttling, whispering, ancient language of energy (long faint sighs across the millennia), you have to shut out the noise of the marketplace. You flip yourself out deliberately. Voluntary holy alienation. You can’t serve God and Caesar. You just can’t.

That’s why the wizards who have guided and inspired human destiny by means of revelatory vision have always been socially suspect. Always outside the law. Holy outlaws. Reckless, courageous outlaws. Folklore has it that 43 federal agents were assigned to His case before He was arrested on the day before Christmas, 1967. They have to stop this wild man with jingling bells or He’ll turn on the whole world. His Christmas acid could have stopped the war.

Messianic certainty. A.O.S.3 is the most moralistic person I have ever met. Everything is labeled good or bad. Every human activity is either right or wrong. He is, in short, a nagging, preaching, intolerable puritan. Right to Him is what is natural, healthy, harmonious. Right gets you high. Wrong brings you down.

Meat is good. Man is a carnivorous animal, but eat your meat rare.

Vegetables are bad. They are for smoking, not eating. God (or the DNA code) designed ruminants and cud chewers to eat leaves. And man to eat their flesh.

Psychedelic drugs are good.

Alcohol is bad. Unhealthy, dulling, damaging to the brain. A “down” trip. He explains this in ominous chemical warnings. I always feel guilty drinking a beer in front of him.

Showers are good. Clean.

Baths are bad. You soak in your own dirt, and your soft pores sponge up foul debris, in a lukewarm liquid, an ideal nutrient for germs.

Rock ’n’ roll is good.

Science fiction is bad. Screws up your head. Takes you on weird trips.

Long hair is good. Sign of a free man.

Short hair is bad. Mark of a prisoner, a cop, or a wage slave.

Smoking is bad.

Marijuana is good.

Sex is good.

Sexual abstinance is insane.

He is now sitting against the wall, talking quietly. The red glow flickers on His round glasses. He is a mad saint.

At the higher levels of energy, beyond even the electronic, there is no form. Form is pure energy limiting itself. Form is error.

On one trip they (I’ll refer to “they” for lack of a better term), the higher intelligence, beckoned me to leave the living form and to merge with the eternal formless which is all form, and I was tempted. Eternal ecstasy. But I declined regretfully. I wanted to stay in this form for a while longer.

Why?

Oh, to make love. Balling is such a friendly, tender, human thing to do.

How about eating?

Oh, yes, that’s tender, too.

Okay. Let’s go to a restaurant.

Owsley is a highly conscious man. He is aware at all times of who he is and what’s what. Aware of his mythic role. Aware of his past incarnations. Aware of his animal heritage which he wears, preeningly and naturally, like a pure forest creature. His sense of smell. Owsley carefully selects and blends perfumes for himself and his friends. Your nose always recognizes Owsley. Oh, some sandalwood, a dash of musk, a touch of lotus, a taste of civet.

I talked to Him once on the phone after a session. He was in His customary state of intense excitement. “Listen, man, I saw clearly my mystic Karmic assignment. I am Merlin. I’m a mischievous alchemist. A playful redeemer. My essence name is A.O.S.3.”

Like any successful wizard, A.O.S.3 is a good scientist. Radarsensitive in His observations. Exacting, meticulous, pedantic about His procedures. He has grandiose delusions about the quality of His acid. “Listen, man, LSD is a delicate, fragile molecule. It responds to the vibrations of the chemist.”

He judges acid and other psychedelics with the fussy, patronizing skill of a Bordeaux wine taster. He is less than kind to upstart rival alchemists. But no jeweler, goldsmith, painter, sculptor, was ever more scrupulous about aesthetic perfection than A.O.S.3.

And like any good journeyman-messiah, His sociological and political perceptions are arrow straight. As do all turned-on persons, A.O.S.3 agonizes over the pollution of the living fabric. He, as well as anyone, sees the mechanization. The robotization.

Metal is good. It performs its own technical function. Metal has individuality, soul.

Plastics are evil. Plastic copies the form of plant, mineral, metal, flesh but has no soul.

Owsley’s life is a fierce protest against the sickness of our times which inverts man and nature into frozen, brittle plastic. Only a turned-on chemist can appreciate the horror, the ultimate blasphemous horror of plastic.

Owsley is unique. He is himself. His life is a creative struggle for individuality. He longs for a social group, a linkage of minds modeled after the harmonious collaboration of cells and organs of the body. He wants to be the brains of a social love body. The ancient utopian hunger. Only a turned-on chemist can appreciate God’s protein plan for society.

A.O.S.3 is that rare species, a realized, living, breathing, smelling, balling, laughing, working, scolding man. A ridiculous, conceited fool, God’s fool, dreaming of ways to make us all happy, to turn us all on, to love us and be loved.

SEAL OF THE LEAGUE

5

M.I.T. Is T.I.M. Spelled Backward*

An interview conducted by Jean Smith and Cynthia White for Innisfree, the MIT monthly journal of inquiry, published by Massachusetts Institute of Technology students.

It was a beautiful autumn Saturday, with the leaves at their psychedelic best, as we drove up to the

large mansion which Dr. Leary and his 30 religious cohorts call home. We arrived as a house meeting was breaking up.

Dr. Leary was in his normal dress (white shirt, white slacks and red socks) and was quite warm and receptive. A half-hour delay before the interview gave us time to take in his home and meet some of the workers, who were preparing for the upcoming Tuesday celebration at New York’s Village Theater.

The house was beautifully well kept, with a minimum of traditional furniture and a pleasant abundance of creative artwork all around. The faded tapestries of a flower-type design that had covered the walls for decades were attractively renovated with bright paint in many colors. Even the pay phone in the stairwell was painted in weird green swirls. On the wall next to the door on the way out was an appropriate sign saying, “Those who don’t know talk, and those who know don’t talk.”

The house was alive with small children, whose presence added all the more vitality to the place. The older workers, most of them our age, seemed generally affable, good-humored and well-educated, and certainly dedicated to their artistic and religious endeavors.

After a pleasant buffet of apple cider and nonpsychedelic mushrooms over rice with salad, Dr. Leary came down and invited us into his office. The half-hour downstairs had broadened our perspectives, but the greatest broadening was yet to come.

INNISFREE: Dr. Leary, one of your comments in your Playboy interview was that if you take LSD in a nuthouse, you will have a nuthouse experience. The modern student seems to be in a rat race and may not feel he can spare more than a day, say a Saturday, for a “trip.” If a student were to take LSD in this rat race environment, would he have a rat race experience?

LEARY: Well, you’re asking for a wild generalization. No one should take LSD unless he’s well prepared, unless he knows what he’s getting into, unless he’s ready to go out of his mind; and his session should be in a place which will facilitate a positive, serene reaction, and with someone whom he trusts emotionally and spiritually.

INNISFREE: When you were experimenting at Harvard, did you find that students were less prepared to go out of their minds?

LEARY: Well, I never gave drugs to any student at Harvard, contrary to rumor. We did give psychedelic drugs to many graduate students, young professors, and researchers at Harvard. These people were very well trained and prepared for the experience. They were doing it for a serious purpose, that is, to learn more about consciousness, the game of mastering this technique for their own personal life and for their professional work.

INNISFREE: Did you ever publish any of your findings from your Harvard stay?

LEARY: Yes, we have published over 35 scholarly and scientific articles. Many of these were based on our Harvard studies: statistical studies, questionnaire studies, descriptions of our rehabilitation work with prisoners, experimental work in producing visionary and mystical experiences, and so forth.

INNISFREE: One of the greatest areas of controversy in regard to LSD is that many people fear, Professor Teuber at MIT for one, that from taking LSD you might have recurrences of the psychosis without further ingestion of the drug. Would you like to comment on this?

LEARY: Number one, I can’t agree with the word psychosis. The aim of taking LSD is to develop yourself spiritually and to open up greater sensitivity. Therefore the aim should be to continue after the session the exciting process you have begun. We’re delighted when people tell us that after their LSD sessions they can recapture some of the illumination and the meaning and the beauty. Psychiatrists think they are creating psychoses; therefore, they would be alarmed at having the experience persist. We know that we are producing religious experiences, and we and our subjects aim to have those experiences endure. And if Professor Teuber’s worried about the fact that nobody knows exactly what LSD does, and I share that worry, we must realize that scientifically we are not sure of what thousands of energies which we ingest or surround ourselves by are doing: gas fumes, DDT, penicillin, tranquilizers. Nobody knows how these work, what effects they’ll have not only on the individual but also on the genetic structure of the species. There are risks involved whenever you take LSD. Nobody should take LSD unless he know’s he’s going into the unknown. He’s laying his blue chips on the line. He’s tampering with that most delicate and sacred of all instruments, the human brain. You should know that. But you know that you’re taking a risk every time you breathe the air, every time you eat the food that the supermarkets are putting out, every time you fall in love for that matter.

Life is a series of risks. We insist only that the person who goes into it knows that it’s a risk, knows what’s involved, and we insist also that we have the right to take that risk. No paternalistic society and no paternalistic profession like medicine has the right to prevent us from taking that risk. If you listen to neurologists and psychiatrists, you’d never fall in love.

INNISFREE: A friend of ours told us that he had recurring hallucinations at a time when he really didn’t want them and didn’t expect them. Are these uncontrollable replays common?

LEARY: I think that everyone who takes LSD is permanently changing his consciousness. That is, there are going to be recurrent memories and recurrent reactions when you hear the same music, when you’re with the same people, when you walk into the same room. Any stimulation may set off a memory. Now a memory is a live, chemical-molecular event in your nervous system. When you take LSD, you’re changing that system to a small degree. Now most people are delighted when this happens.

In any thousand people, or perhaps hundred, there’s a professional full-time worrier. Now when this person takes LSD, he’s going to wonder if he’s going crazy, he’s going to worry that he’s insane, he’s going to worry about brain damage, he’s going to worry about controlling it. Worriers, of course, are people who want to have everything under control. And life is not under control. Life is a spontaneous, undisciplined, unsupervised event. Your worrying person is going to lay his worrying machinery on LSD.

INNISFREE: You mentioned religion a few minutes ago. Professor Huston Smith of MIT has suggested that the drug-induced religious experience may not be a truly genuine one.

LEARY: You’re now sitting in a religious center. About 30 people are devoting their lives and energies to a full-time pursuit of the Divinity through the sacrament of LSD. You’re calling our sacramental experience psychotic. LSD, the psychedelic experience, is a religious experience. It can be if the person is looking for it, and can be if the person is not looking for it and doesn’t want it. Professor Smith has on several occasions stated his belief that the drug-induced experience is a religious experience. He has questions, as I understand it, about how this can be used and how well we are applying our religious experiences, but he does not doubt that they are religious experiences. Now the religious experience is beyond any creed or ritual, any myth or metaphor. People use different interpretations, different metaphors to describe their religious experience. A Christian person will take LSD and report it in terms of the Christian vocabulary. Buddhists will do likewise.

INNISFREE: Is it true that you yourself are Hindu?

LEARY: Our religious philosophy, or our philosophy about the spiritual meaning of LSD, comes closer to Hinduism than to any other. Hinduism—again, it is difficult to define Hinduism—recognizes the divinity of all manifestations of life, physical, physiological, chemical, biological, and so forth. So that the Hindu point of view allows for a wide scope of subsects. To a Hindu, Catholicism is a form of Hinduism.

INNISFREE: Your descriptions of the psychedelic experience sound very much like Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha. How much have you been influenced by his writings?

LEARY: We’ve been influenced very much by Hermann Hesse’s writings. Of course, once you finally get into the field of consciousness, in the philosophic and literary interpretations of the consciousness, then everyone agrees. Everyone is in basic agreement about the necessity of going out of your mind, going within, and about what you find once you ge

t there. The metaphors change from culture to culture. The terminology is different. But every great mystic and every great missionary reports essentially the same thing: the eternal flow, timeless series of evolutions, and so forth, and Hermann Hesse is one of the great visionary spokesmen of the twentieth century. We made it very explicit in our first psychedelic celebration in New York that we were addressing ourselves to the intellectual who is entrapped in his mind, and we were using as our bible for that first celebration Steppenwolf, by Hermann Hesse. The next psychedelic celebration was based on the life of Christ, and we used the Catholic missal as the manual for that. But each one of these great myths is based on a psychedelic experience, a death-rebirth sequence.

INNISFREE: Is each of these sessions supposed to appeal to a different kind of person?

LEARY: Each celebration will take up one of the greatest religious traditions. And we attempt to turn on everyone to that religion. And we hope that anyone that comes to all of our celebrations will discover the deep meaning that exists in each of these. But in addition to that, we hope that the Christian will be particularly turned on by our Catholic LSD mass, because it will renew for him the metaphor which for most of us has become rather routine and tired.

INNISFREE: Where did you get for your foundation the name Castalia?

LEARY: Castalia was taken from Hermann Hesse’s novel Magister Ludi. The Castalia brotherhood in that novel was one of scientist-scholars who were attempting to bring together visionary mysticism and modern science and scholarship. They would also meditate and use the techniques of the East in order to bring together the bead game itself, a means of weaving together poetry, music, mathematics, science, and unifying them. We attempt to do the same. Our psychedelic celebrations and the lectures that Dr. Metzner and I have been giving in the last two years are very much like the bead game. We attempt to weave together modern techniques like electronics and modern scientific theories, pharmacology and biogenetics, with many different forms of Eastern psychology. It’s very clearly a bead game that we are weaving in these celebrations. The aim is to turn on not just the mind, but to turn on the sense organs, and even to talk to people’s cells and ancient centers of wisdom.

Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out

Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out